a weblog sharing info on outdoor skills and campfire musing by a guy who spends a bunch of time in pursuit of both

CULTURE

WHERE -

TALES ARE TOLD OF

Welcome to Roland Cheek's Weblog

Roland is a gifted writer with a knack for clarifying reality. Looking forward to more of his wisdom

- Carl Hanner e-mail

Aldo Leopold wrote in A Sand County Almanac: "When I first saw the West, there were grizzlies in every major mountain mass." Then he added, ". . . of the 6,000 grizzlies officially reported as remaining in areas owned by the United States 5,000 are in Alaska. Only five states have any at all. There seems to be a tacit assumption that if grizzlies survive in Canada and Alaska, that is good enough. It is not good enough for me. . . . Relegating grizzlies to Alaska is about like relegating happiness to heaven; one may never get there."

To access Roland's weblog and column archives

Tip o' the Day

I like to watch wildlife. Jane is a wildlife aficionado, too. We cut our teeth looking for elk. But spotting bears eventually shouldered even a primary desire to see a massive bull elk aside. We're into not just any bear, though! What turns our crank is grizzly bears.

Spot a herd of elk and both of us will focus our glasses on the herd bull to the detriment of a passel of cows. But there's no male chauvinism when it comes to viewing grizzly bears -- we get just as much kick out of watching a young sow splashing in a swamp as we do ooh-ing and ahh-ing at a huge boar scratching his back on a lone pine tree. Or cubs frolicking in fresh snow. Or a couple of delinquent two-year-olds knocking over their first yellowjacket nest.

Strangely, wolves have never meant as much to me, probably for the simple reason that I can't tell the difference between a wolf and an Alaskan husky dog -- except for the places they roam. And . . . except for a wolf's glistening yellow eyes. See a wolf from a distance, however, and I always wonder how well he'd pull a sled in the Iditarod.

Not so grizzly bears! There's no mistaking a grizzly for anything but . . . well . . . a grizzly.

A bull elk is regal. A full-curl bighorn ram inspires admiration. But a grizzly? He's the Marine Band of the animal world. He swaggers with the calm indifference of an animal who knows he has nothing left to prove. Though he may really believe us superior animals, he's in no way reconciled that we are masters.

I thrill easily: to the eyecatching, erratic flight of a mountain bluebird migrating south in mid-October along the snowbound crest of the Chinese Wall; to the Clark's nutcracker waddling from huckleberry bush to huckleberry bush, his beak stained in purple as he, too, joined the juicy feast in the patch I'd thought all my own; to a weasel scampering again and again to the top of our tent so he could slide down the plastic cover. But there's nothing -- nothing! -- to equal the sight of a grizzly ambling from a forest fringe with the intent of grazing on the lush grass of a peatmoss bog.

Look for them in the peatbog or swamp in the spring. They especially like fresh green skunk cabbage, cattail roots, and sedge grass. You may wish also to check avalanche paths for carcasses of dead ungulates killed in a snowslide. Finding a dead elk or deer or mountain goat fulfills the wildest dreams of most hungry bears fresh from hibernation.

* * *

An upstanding lady whom I've never met sent the following email with the subject "Question About Bears":

I am enjoying "Learning To Talk Bear." I have read many books about bears, am addicted to Animal Planet documentaries about bears and have seen them in Yellowstone in Montana! I have a question that I have never seen answered anywhere . . . bear cubs that grow up together, same sex or even a male and female sibling . . . as adults, do they recognize or remember each other? Would male and female siblings mate or do they have an innate sense or true memory that they are related? Would an adult male sibling respect the boundaries of its female sibling and not be a threat to her cubs if they met up later as adults? Would male siblings fight over territory or "fishing spots"? I would appreciate any insights you could give me. __________________

Nancy - Tough question. For a definitive answer, you'll probably want to go to a biologist, a researcher who's done the work. Now having said that, I'll go ahead and tell you what I think. . . . Given the known fact that grizzly bears will usually try to establish their own territory outside of their mother's home range, the odds of their getting into close encounters with a sibling is at least halved. Then to note that every male bear embraces a much larger territory than females, again the odds of a chance encounter is further diminished. All bears are inherently shy, avoiding encounters with other bears when possible, only deviating from that during mating times, or when local food supplies are so abundant an individual bear needs not worry about protecting his or her protein. Mother bears are, of course, extremely aggressive in protecting their cub(s) and few males would care to chance a raid on such females. Would they snap up a cub in an opportunistic moment? I think so. Would they prey on a female herself? Only in certain circumstances, such as an injured sow, or one near death from old age -- the Rottweiler Bear in my book, Learning To Talk Bear, was known to have done so. But probably most hungry grizzlies would prey on a dead bear -- even members of the family. For reference, see "The Grizzly Daughter I Never Had" in the same book; or Chocolate Legs devouring her own dead cub in my book Chocolate Legs.

I haven't really answered your questions have I? Will a brother and sister mate? I don't know. Probably. Under certain conditions -- such as critically low population densities. But rarely. While we're at it, though, why not wonder about sons with mothers? Or fathers with daugthters. Sorry I can't be more helpful. Samezever, Roland

HOW DOES GOD DO IT?

I suppose it's true that I began my outdoors career stalking polywogs and frogs and garter snakes in the marsh that spread just across the barbed wire fence from the rural school we kids attended. And while it's true clambering over that fence invariably led to having my hinder paddled, I wasn't the only repeat offender. Nor was I the only one to surreptitiously introduce reptiles and amphibians to the seats of female higher education.

Later I graduated to hunting and fishing, learning to first stalk trout along the creeks flowing through my family's farm, then moving on to hill country deer, and eventually to pursue elk amid the mountains west of my home.

Wildlife was, by my late teens, the primary focus (with occasional detours to investigate the turn of a pretty lady's ankle). But concentration on bucks and bulls was near-total and I learned to pick out the twitch of an ear amid a forest of young firs, the outline of a body screened by a rhododendron thicket, a gray swatch amid a distant brown-grass hillside.

Of a necessity, I developed a reasonably unerring sense of direction and a driving need to view what was over the next hill. One spectacular vista led to another until that gnawing need turned into a burning desire to see as many of God's best places as one lifetime might accommodate. Eventually that growing expertise in mountain travel, hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing developed into a career as a guide leading others to wilderness adventure.

My wife Jane's interest in flowers led us both into wildflower (and eventually plant) identification. But that focus on vegetation, I found, blunted my wildlife viewing edge. Still, I soldiered on. Then came an interest in rocks.

By employing a geologist as landform interpreter for some of our wilderness trips, I learned a bunch about rocks--boy, did I! I learned about thrust and tension faulting and the mountain building process, then how soil developed that plants found attractive that, in turn, attracted deer and elk.

Still, additional focus brought additional dilution of focus on the areas of expertise I may have thought I'd already mastered. For example, one can miss a tiny orchid, a fairy slipper, growing in a wet spot in a rock cleft if he's altogether concentrated in searching for fossils amid those same rocks. Spot an ear twitch when one is memory-cataloging the varieties of wildflowers growing in a swale? Forget it.

I even sometimes caught myself paying more attention to puzzling how distant mountains were formed than in ogling the sheer magnificence of the mountain vistas themselves.

What of water. It's not enough to know water runs downhill--what about when it cuts through a limestone wall, like the one a Gateway Gorge, up the Flathead's Middle Fork? Or how about when one stream captures another through the gradually wearing away of a ridge? Can volcanic eruptions alter stream flows?

Then there're the lakes, oft times carved by glaciers, from gargantuan Flathead Lake (and the Great Lakes) to tiny My Lake beneath the rock formation known as the Chinese Wall?

How did fish get over barrier falls into some high mountain lakes, or upper river reaches? My God! Is there no end to it all?

Even thinking-time was disrupted. Instead of conjuring up images of bull elk standing at a mineral lick, I spent most of my waking hours strategizing ways to analyze soil and water from that lick in order to discover the mineral attractant to the creatures--and why?

What browse plants were primary food souces for deer? What made them more palatable? Where did they grow? The aspect? In shade or out? Must they be frosted before turning palatable?

What tree species grew where? Dry site or wet? Why did some mountainsides receive less rainfall than others? Why was winter snow depths greater on some mountains than others? Why do bears claw certain trees, yet leave others alone? Why do elk rub some saplings during the rut while leaving others alone? What about deer scrapes? Their location? Their size?

Above all, I leaned I cannot possibly focus on everything that's out there.

Now I'm wondering how God does it?

Roland Cheek wrote a syndicated outdoors column (Wild Trails and Tall Tales) for 21 years. The column was carried in 17 daily and weekly newspapers in two states. In addition, he scripted and broadcast a daily radio show (Trails to Outdoor Adventure) that aired on 75 stations from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific Ocean. He's also written upwards of 200 magazine articles and 12 fiction and nonfiction books. For more on Roland, visit:

www.rolandcheek.com

Recent Weblogs

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

There's a bunch of specific info about Roland's books, columns, radio programs and archives. By clicking on the button to the left, one can see Roland's synopsis of each book, read reviews, and even access the first chapter of each of his titles. With Roland's books, there's no reason to buy a "pig in a poke."

for detailed info about each of Roland's books

Read Reviews

Read their first chapters

For interested educators, this weblog is especially applicable for use in environmental and government classes, as well as for journalism students.

Roland, of course, visits schools. For more information on his program alternatives, go to:

NEXT WEEK:

WHEN ACTION BECOMES IMPERITIVE!

www.campfireculture.com

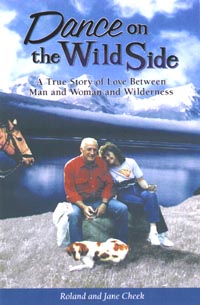

Dance On the Wild Side is the story of Jane's and Roland's life as guides in the Bob Marshall Wilderness

source links for additional info

to send this weblog to a friend

to tell Roland what you think of his Campfire Culture weblog

to visit Roland's newspaper columns and weblog archives

To read reviews, or the first chapters of these and other Roland Cheek books

And his book about elk